Entering the European market for turmeric for food additives

As an exporter of turmeric targeting the European market, you must meet strict food safety and purity standards. You should also demonstrate full traceability and transparent sourcing practices. Buyers in Europe want suppliers who can provide complete documentation. That includes certificates of analysis and curcumin specifications. Your competition comes from Indian suppliers and from emerging exporters in southeast Asia and Latin America. To succeed, you need to position yourself as a reliable, certified supplier. Show you can meet both regulatory requirements and demand for sustainable ingredients.

Contents of this page

- What requirements and standards must turmeric for food additives meet to be allowed on the European market?

- Through what channels can your turmeric for food additives enter the European market?

- What competition do you face on the European turmeric for food additives market?

- What are the prices of turmeric for food additives in the European market?

1. What requirements and standards must turmeric for food additives meet to be allowed on the European market?

To enter the European market, turmeric must comply with European Union (EU) regulations. These rules differ, depending on whether the turmeric is classified as a colouring food, a food additive or an oleoresin. They cover purity criteria, maximum residue levels for pesticides and proper classification, labelling and packaging amongst other things. Many European buyers trust you to strictly follow these regulations. They also expect organic certification, fair-trade credentials and proven sustainability. Traceability and ethical sourcing are also important.

What are mandatory requirements?

European regulations seperate turmeric as a colouring food and as a food additive (curcumin E100 and oleoresin). Both must meet strict purity criteria, contaminant limits and labelling requirements. To follow these rules, you should have detailed documentation, laboratory testing and proper classification. Without them, your shipments could be rejected at the border or included in the EU’s Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed.

Food safety

Under EU legislation,colouring foods and colours used as food additives are clearly seperated. This directly applies to turmeric.

- Colouring foods (or colouring foodstuffs) are food ingredients that provide colour but are recognised and consumed as food. Dried turmeric and turmeric juice concentrate, for example, are obtained from edible parts of the plant’s root using non-selective processing methods. These products retain all the characteristics of food (flavour, aroma and nutritional components). As such they are classified as colouring foods, not additives.

- On the other hand, when turmeric undergoes selective extraction to isolate the yellow pigment curcumin, the resulting substance is considered a colour additive (Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008). Curcumin as an additive is specifically used to add or restore colour in food products. Importantly, it does not retain the broader characteristics of the original turmeric root. Curcumin (E100) and turmeric oleoresin are both examples of such additives.

Both forms must comply with EU regulations covering food safety, purity criteria, extraction methods, contaminant limits and labelling. Here are some of the key regulations:

- General food law – Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 sets baseline food safety principles.

- Food additives – Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 defines authorised additives and usage levels.

- Purity standards – Regulation (EU) No 231/2012 sets purity criteria for food colours.

- Contaminants – Regulation (EC) No 203/915 sets maximum levels for heavy metals and mycotoxins.

- Pesticides – Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 sets maximum residue levels.

- Labelling – Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 requires proper classification, hazard labelling and packaging.

Specific requirements for food colourants

As well as the general safety rules mentioned above, food colourants must also meet specific purity and solvent residue standards. These are described in the Annex to Regulation (EU) No 231/2012. Each authorised colour has its own standards. For curcumin E100, the purity criteria are listed in the table below.

Table 1: Purity criteria for curcumin E100

| Parameter | Limit |

|---|---|

| Solvent residues | Max. 50 mg/kg (combined total for ethylacetate, acetone, methanol, ethanol, hexane, etc.) |

| Dichloromethane | Max. 10 mg/kg |

| Arsenic | Max. 3 mg/kg |

| Lead | Max. 10 mg/kg |

| Mercury | Max. 1 mg/kg |

| Cadmium | Max. 1 mg/kg |

Source: ProFound, 2025

Due to the strict limits, many manufacturers are shifting toward solvent-free extraction methods such as steam distillation, especially for organic markets. Solvent-free processing may not be possible for turmeric, however, depending on the pigment’s solubility and stability.

Specific requirements for oleoresins

When oleoresins are used as flavourings, they must comply with food safety rules that focus on the presence of contaminants across three main categories.

- Physical – Foreign materials such as dirt, plastic or metal shavings;

- Chemical – Pesticide residues;

- Biological – Microbial contamination, such as bacteria or mould.

The use of concentrated extracts like oleoresins creates specific challenges. Even trace amounts of pesticide residues in the raw spice can become magnified in the final oleoresin. This makes it harder to meet EU maximum residue limits (MRLs). As a result, more and more European buyers are asking for the following documents:

- Organic certification;

- Detailed lab test reports;

- Verification that the product complies with Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 (covering MRLs of pesticides in or on food and feed of plant and animal origin).

Examples of RASFF alerts related to turmeric and curcumin (2020-2025)

Any deviation from safety thresholds can result in RASFF alerts, rejection at the port of entry or commercial penalties. Between January 2020 and July 2025, 14 RASFF alerts related to turmeric and curcumin were issued. Eleven of these involved exports from India. They covered such problems as unauthorised dyes, pesticide residues, traceability errors, undeclared allergens and inaccurate documentation. There were also 4 alerts for salmonella and 7 alerts for aflatoxins between 2020 and 2025. These emphasise the EU’s strict limits on microbial and chemical contaminants in turmeric products.

The alerts show the importance of strict quality control, full traceability and contaminant testing.

Table 2: Examples of RASFF alerts involving turmeric and curcumin, 2024-2025

| Issue reported | Origin/route | Severity | Risk type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mismatched batch numbers in the packaging and the official certificate | India to Latvia | Not serious | Traceability |

| Rhodamine B (unauthorised dye) in turmeric | India to Germany | Potentially serious | Chemical contamination |

| Chlorpyrifos (unauthorised pesticide) in ground turmeric | Belgium to France | Potentially serious | Pesticide residue |

| Methyl yellow (unauthorised colourant) in turmeric powder | India to Germany via Italy | Serious | Chemical contamination |

| Undeclared broad beans (favism risk) in turmeric | Lebanon to Sweden | Potentially serious | Allergen/labelling |

| Incorrect analytical report for turmeric | India to Latvia | Potential risk | Documentation |

Source: RASFF, 2025

Tips:

- Prevent pesticide residues from triggering an RASFF alert. Source your turmeric only from certified farms with documented good agricultural practices.

- Avoid traceability violations. Document your batches correctly and make sure that certificate numbers match those on your packaging exactly.

- Identify emerging contamination risks. Check the RASFF portal frequently for turmeric-related alerts and adjust your quality control procedures accordingly.

Use of enzymes and extraction solvents

The rules for the use of enzymes and extraction solvents in the production of colouring foods, along with their conditions of use and MRLs, are outlined in Directive 2009/32/EC. Annex I of that directive contains a list of authorised extraction solvents for use in food, together with their specific conditions of use. Regulation (EC) 1332/2008 lists enzymes that may be used in food production, including colouring foods. Since there is currently no EU list of authorised food enzymes, national rules apply.

The following solvents are authorised by the EU for oleoresin extraction, in compliance with good manufacturing practice:

- Propane;

- Butane;

- Ethyl acetate;

- Ethanol (considered the optimum organic solvent for curcumin preparation);

- Carbon dioxide;

- Acetone;

- Nitrous oxide.

What additional requirements and certifications do many buyers expect?

Aside from EU requirements, many buyers have their own additional standards regarding classification, labelling and packaging.

Classification, labelling and packaging requirements for colourants and oleoresins

Both curcumin (E100) and turmeric oleoresin are subject to the CLP Regulation (Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 on the classification, labelling and packaging (CLP) of substances and mixtures). This implements the Globally Harmonised System (GHS) in the EU and requires suppliers to check if their product poses any risks to human health or the environment.

The table below summarises the key differences in CLP requirements between curcumin colourants and oleoresins.

Table 3: Key differences in CLP requirements between curcumin E100 and turmeric oleoresin

Aspect | Curcumin E100 (colourant) | Turmeric oleoresin (flavouring) |

|---|---|---|

| Legal category | Food additive (Reg. 1333/2008) | Natural flavouring (Reg. 1334/2008) |

| Declared as | ‘Colour: curcumin (E100)’ | ‘Natural flavouring’ or ‘natural turmeric flavouring’ |

| CLP hazard risk | Sometimes classified as hazardous (concentration-dependent) | Often classified as hazardous; must follow full CLP compliance |

| Labelling focus | E-number required; cannot be labelled ‘natural’ | Can use ‘natural’ if all inputs are 100% natural |

| Organic labelling | Optional | Required if certified; must include logo, origin, certifier code |

| Packaging needs | Light/oxygen protection; solid or liquid formats | Leakproof, non-reactive, often filled with inert gas |

| Typical packaging | 25 kg bags, HDPE drums, IBCs | Galvanised or lined drums, aluminium, glass |

Source: ProFound, 2025

CLP requirements for curcumin as a food colourant

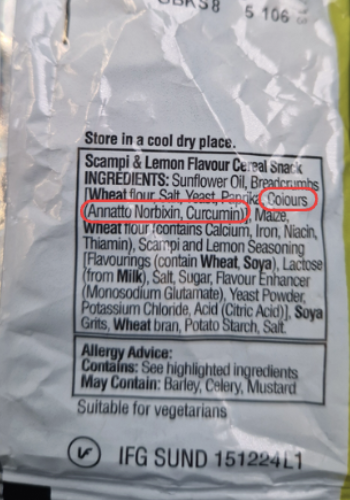

Curcumin used as a food colourant is classified as a food additive (Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008). The E number is E100 and it is known to be a natural additive. It is also treated as an additive rather than a food ingredient. This means it must be clearly stated in the ingredient list of any final food product it is used in.

Labelling requirements for curcumin are shown in Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 and Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011. These state that food additives must be labelled with their functional category (in this case, ‘colour’). This is followed by either the specific name ‘curcumin’ or the corresponding E number, ‘E100’. It is important to note these are requirements for finished products.

For example, a ingredient list that follows the rules might read: ‘Colour: Curcumin’ or ‘Colour: E100’.

Figure 1: Example of curcumin listed as a food colourant on a food product

Source: Open Food Facts, 2025

Curcumin extract is not considered a ‘colouring food’ because it comes from selective extraction of the pigment. Unlike turmeric powder, it cannot be labelled as a food ingredient. Instead, it must be listed on packaging as a colour additive. This distinction is particularly relevant in relation to clean-label trends. Many consumers are wary of ‘E numbers’ (European additive codes) – even those derived from natural sources. For this reason, some manufacturers prefer to list colourings by their botanical or known name, such as ‘curcumin’. This both avoids the use of E numbers and responds to consumer demand for simpler ingredient lists.

In terms of packaging, curcumin extract is available in both solid and liquid forms.

- Solid form – Typically packed in 25-kilogram paper or foil-lined bags, sealed to protect against moisture and oxidation. These bags are palletised and shrink-wrapped for stability during shipping;

- Liquid form – Often packaged in high-density polyethylene (HDPE) drums, aluminium barrels or intermediate bulk containers (IBCs) with oxygen-resistant linings. Because curcumin is highly sensitive to light and oxygen, the packaging must provide sufficient barrier protection to maintain colour quality. Some suppliers use nitrogen flushing to fill the headspace of containers and so reduce oxidation.

CLP requirements for turmeric oleoresin as a flavouring

Turmeric oleoresin, when used as for flavouring, falls under Regulation (EC) No 1334/2008 on flavourings and food ingredients that add flavour. Turmeric oleoresin is considered a natural flavouring preparation when it is derived entirely from turmeric using approved extraction methods.

When labelling turmeric oleoresin on the final product, the rules differ from those for food additives. If the oleoresin consists entirely of natural flavouring preparations or substances, it can be described on the label as a ‘natural flavouring’. If the flavour comes specifically from turmeric and no other source, it may be labelled as ‘natural turmeric flavouring’. However, these designations are only permitted if the entire flavouring component meets the EU’s definition of ‘natural’.

Because oleoresins are concentrated and often chemically active, they are more likely to be classified as hazardous substances under the CLP Regulation. If this is the case, the product must include hazard pictograms, standard risk phrases and other relevant safety information.

Figure 2: Hazard symbols for turmeric (Curcuma longa)

Source: ECHA Chem, 2025

Packaging for oleoresins must be robust and sealed in a way that prevents leaks or accidental exposure. Packaging materials must be non-reactive and approved for use in food contact applications. Common materials include aluminium, lined or lacquered steel and, for smaller quantities, glass. Polypropylene and other plastics are generally avoided, especially by European buyers who are concerned about quality risks.

To preserve the chemical and aromatic integrity of turmeric oleoresin, suppliers often fill the headspace of the container with inert gases such as nitrogen or carbon dioxide. This prevents oxidation, which can degrade the oleoresin’s flavour and colour.

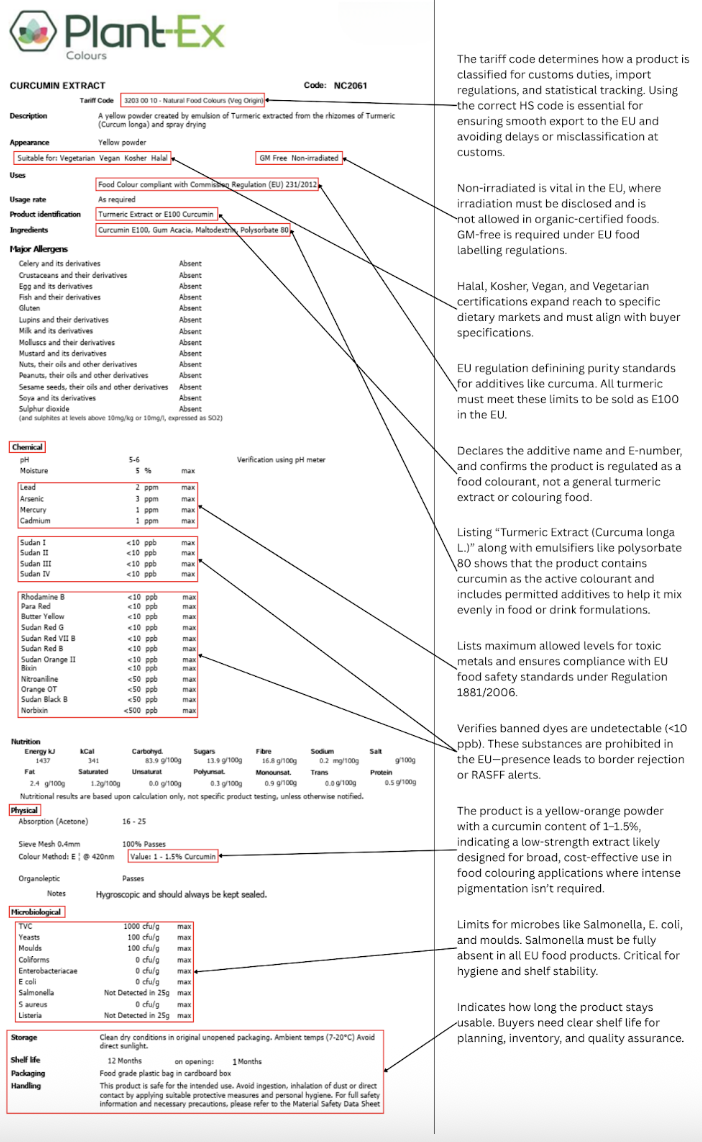

The figure below shows a European buyer’s actual specification sheet for curcumin extract. It reveals what they expect and how that is communicated to potential suppliers.

Figure 3: Real-world example of a curcumin extract specification sheet, by Plant-Ex

Source: Plant-Ex, 2025

Tip:

- For further information, read the CBI study on requirements for natural food additives to be allowed on the European market.

What are the requirements for niche markets?

Beyond the EU regulations, many European buyers in premium market segments expect their suppliers to provide sustainability credentials, ethical sourcing documentation and voluntary certifications like organic or fairtrade.

Sustainability

European buyers of turmeric-based food additives are under increasing pressure to meet high sustainability and transparency standards. On the one hand this trend is driven by regulations like the European Green Deal and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), and on the other by rising consumer demand for ethically sourced ingredients.

Although the policies mentioned do not apply directly to exporters outside the EU, they do have a significant indirect impact. If you supply turmeric additives to European companies, you will be expected to comply with their sustainability and due diligence requirements.

One priority for buyers is the ability to trace turmeric back to its source. They want clear evidence of environmentally and socially responsible practices throughout the supply chain. For example:

- Responsible sourcing of turmeric (no deforestation or overharvesting, etc.);

- Fair labour conditions during farming and processing;

- Minimal environmental impact in extraction and packaging.

Buyers are increasingly looking for suppliers who have formal corporate social responsibility (CSR) policies. Tools such as Supplier Ethical Data Exchange (Sedex) can support you in meeting ethical sourcing expectations and improving your visibility to buyers who value that effort.

Certifications

If you are supplying turmeric as a food additive, you can target specific niche market segments in Europe that highly value ethical and sustainable sourcing. These include the organic and fair-trade categories. Each niche has its own standards and certifications, which can increase your product’s appeal and value in the European market.

To label turmeric as organic in the EU, your product must comply with its Organic Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2018/848). This includes strict controls on:

- The use of natural pest-control and weed-control methods;

- Organic soil management;

- Traceability throughout the supply chain;

- Permitted extraction methods (such as water, steam or organic alcohol).

Curcumin that has been extracted using hexane or other non-permitted solvents cannot be certified as organic under EU rules. To be accepted as EU Organic, certification must be issued by an EU-recognised control body.

Fair-trade certification applies to the way your turmeric is grown and sourced. This segment values fair wages, safe working conditions and equitable pricing structures for farmers and processors. Certifications such as Fairtrade International (via FLOCERT) and Fair for Life are widely known in Europe. Fair-trade turmeric can be used to create different product lines that appeal to ethically conscious food manufacturers and consumers.

Figure 4: Examples of niche certification labels

Source: Labelinfo, 2024

Tip:

- Check out the Fair for Life website. Use the certified partners filter to find suppliers who are already part of this scheme. This will give an idea of their performance scores and product categories. You can then also explore their own websites.

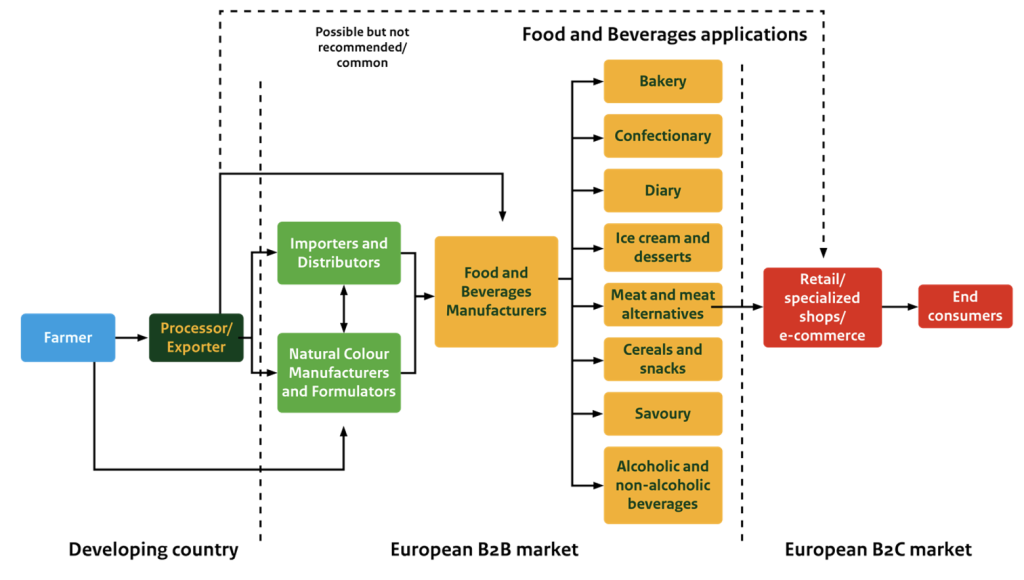

2. Through what channels can your turmeric for food additives enter the European market?

Turmeric enters Europe through three main channels: importers and distributors who handle logistics and compliance; natural colour and flavour manufacturers who process raw turmeric into standardised extracts; and food and beverage companies seeking direct sourcing partnerships.

How is the end market segmented?

Natural colours, including turmeric, are used across a wide range of food segments.

- Turmeric colourant – Used in powdered or water-dispersible extract form. Well-suited for water-based or dry food applications, such as bakery goods, confectionery, dairy products and beverages.

- Turmeric oleoresin – Used mainly in fat-based or processed foods. Found most commonly in savoury dishes, snacks, spice blends and ready-made meals. Valued for its heat and light stability and its ability to disperse well in oil-based formulations.

The chart below shows the wide range of uses for natural colours and oleoresins.

Figure 5: End-market segmentation for natural food colours and oleoresins

Source: Template design by Slidesgo, 2025

The use of natural colours like turmeric is expected to keep growing. This is because visual appeal is a key purchasing factor in food and beverage sales. There is growing consumer demand for transparency, too. 94% of consumers report they are more likely to be loyal to a brand that is ‘completely transparent’.

Buyers are drawn more and more to products made with ingredients they recognise and understand. As a result, turmeric as a food additive is popular mainly for its natural origin and clean-label appeal rather than for any functional health claims.

Turmeric as a food additive

The table below lists the most common food categories in which turmeric (Curcuma longa) is used, and in what form (the food colourant curcumin E100 or oleoresin).

Table 4: Uses of turmeric in food applications

| Category | Product examples | Food colourant | Oleoresin | Functional role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakery | Bread, cakes, cereal bars | ✓ | ✓ | Adds yellow tone; visual appeal in dry goods |

| Confectionery | Gummies, candies | ✓ | Natural substitute for synthetic dyes | |

| Dairy and alternatives | Yoghurt, cheese, plant-based drinks | ✓ | Warm colour tone; matches clean-label demand | |

| Ice cream and desserts | Ice cream, custards | ✓ | Smooth colour integration; enhances visual richness | |

| Meat, meat alternatives and seafood | Processed meats, meat analogues, fish | ✓ | ✓ | Golden hue; enhances appearance in protein-based items |

| Cereals and snacks | Breakfast cereals, granola bars, savoury snacks | ✓ | ✓ | Adds natural tone; suitable for baked and extruded snacks |

| Savoury and ready meals | Soups, curries, sauces, pasta dishes, crisps | ✓ | Enhances visual appeal; complements natural ingredients | |

| Seasonings and condiments | Dry spice blends, table sauces and marinades | ✓ | ✓ | Oil-soluble colour; works well in spice and fat-based carriers |

| Beverages | Turmeric lattes, functional drinks, juices | ✓ | Minimal dosage; mostly for marketing and natural cues |

Source: ProFound, 2025

Figure 6: Food and beverage products containing turmeric colouring or extracts

Source: ProFound, 2025

The choice of form (food colourant or oleoresin) depends on the type of food product it is being used in, the desired processing characteristics and the formulation system (for example, water-based versus oil-based). Each form has distinct properties that are good for different applications in the food and beverage industry.

Curcumin as a food colourant is best suited for:

- Water-based or dry applications, such as yoghurts, beverages, cereals and baked goods;

- Clean-label products, where natural colours that consumers recognise are preferred;

- Heat-processed products, as the colourant is relatively stable under typical cooking temperatures;

- Shorter shelf-life items, where long-term colour stability is less critical.

Oleoresin contains both colour compounds (like curcumin) and aromatic oils. This form is mainly used in oil-based or fat-containing products, where dispersion in oil is required and colour stability is important.

Oleoresin is best suited for:

- Seasonings and condiments, where it disperses well in oil-based spice blends or marinades;

- Meat, seafood and meat alternatives, where it provides uniform colouring during extrusion;

- Bakery goods, particularly those with oil or fat content, like cakes or fillings;

- Snacks such as crisps or extruded products, where an oil coating is used.

Powdered food colourants are often preferred for their cost-effectiveness, their compatibility with a wide range of formulations and their ease of handling during production. They are particularly useful in dry mixes or applications with low oil content. Oleoresins are more stable under heat and light than powdered forms. This makes them ideal for processed foods with longer shelf lives. They also allow for better colour control in oily systems where water-dispersible powders would not blend well.

Through what channels does turmeric for food additives reach the end market?

The main channels to the European market include importers and distributors, natural food colour and flavour manufacturers and formulators, as well as food and beverage manufacturers.

Figure 7: Export value chain for turmeric as a food additive

Source: ProFound, 2025

Importers and distributors

Importers and distributors play an important role in the European trade in natural food colours and oleoresins. This is because many food manufacturers do not have the resources or expertise to source directly from developing countries. Distributors typically require full documentation, including technical data sheets, certificates of analysis and traceability records. Most leading importers and distributors of oleoresins for the European market are in Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, France, Italy and Poland. They include British Pepper and Spices (United Kingdom), Diego Pérez Riquelme e Hijos, Disproquima and EPSA (Spain), Roeper, Rüther Gewürze GmbH, Henry Lamotte Oils GmbH, TER Ingredients, A2 Trading and Brenntag Food and Nutrition (Germany) and Falken Trade (Poland)

Roeper, for example, supplies turmeric derivatives in standardised formats like 5-25 kg UN-approved canisters. It handles everything from sourcing to logistics and distribution. Many such importers are interested in partnerships with reliable suppliers, especially if you can offer strong traceability, certification and consistent quality.

Natural colour manufacturers and formulators

For food colourant applications, the main entry point to the European market is through natural colour manufacturers. These companies purchase turmeric in raw, semi-processed or pigment form. They then process it into colouring ingredients for specific food and beverage products.

Major players like Givaudan, Oterra, Diana Foods, Nactarome and Doehler dominate the market and often acquire smaller local firms to expand their reach. While these large groups lead in innovation, there is still space for medium-sized manufacturers. Especially those who focus on clean-label and natural solutions. These manufacturers sell to food producers across Europe. They are increasingly looking for high-quality, traceable sources of turmeric.

For oleoresin applications, the key buyers are flavour and natural ingredient manufacturers. These companies purchase turmeric oleoresin to create flavour blends or oil-soluble colour systems. They often combine them with other oleoresins like paprika or capsicum. Leading firms such as Givaudan and Symrise formulate customised solutions for different segments of the food and beverage industry. Some manufacturers specialise in both flavouring and colouring, which allows them to offer integrated ingredient systems.

Other interesting firms include Sensient Food Colors, DDW, The Colour House and Naturex (France). Medium-sized manufacturers that also distribute to food and beverage companies are Proquimac (Spain), Bart (Poland), Kanegrade (UK), Holland Ingredients (the Netherlands) and Ringe Kuhlmann (Germany). If you supply turmeric as an oleoresin, interesting flavour manufacturers include Nactis (France) and Treatt (UK).

What is the most interesting channel for you?

Importers and distributors are some of the most accessible and active channels for both turmeric and oleoresin food colourants. Spain is a rapidly growing destination for natural colours. Demand there is increasing due to the country’s large food sector and the rise of Barcelona as a hub for natural colours.

Targeting natural colour and flavour manufacturers is a good idea if your turmeric has high colour intensity or is processed into oleoresins. The flavour industry (more relevant for oleoresins) includes large global groups, but also many small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and family-run companies. These SMEs make up most of the members of the European Flavour Association, and they are often willing to develop long-term sourcing relationships.

3. What competition do you face on the European turmeric for food additives market?

India dominates the European market for turmeric, but several other developing countries are also rising in prominence. Each of these offers its own distinct advantages. From high-curcumin varieties and government support to regional ties and niche positioning, the competition is becoming more diverse.

Which countries are you competing with?

After India, Peru is the second-largest exporter of turmeric to the EU. Other emerging suppliers include Madagascar, which held a 1.4% share of EU imports in 2024, followed by Indonesia (0.9%).

Table 5: Volumes and values of turmeric exports to Europe from selected countries

| Country | Value in 2024 (million €) | % change in value (2020-2024) | Volume in 2024 (metric tonnes) | % change in volume (2020-2024) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | 39.9 | 58.86 | 18,136 | 0.2 |

| Peru | 4.4 | 11.35 | 2,739 | 2.39 |

| Madagascar | 0.84 | 51.53 | 315 | 14.96 |

| Indonesia | 0.46 | 250.77 | 203 | 238.33 |

Source: ITC Trade Map, 2025

Figure 8 compares the two leading exporters of turmeric to Europe.

Source: ITC Trade Map, 2025

Figure 9 shows the development of turmeric exports to Europe from selected countries over the past 5 years. India has been omitted to allow for a more balanced view of the three other focus countries.

Source: ITC Trade Map, 2025

India

India remains the largest exporter of turmeric to Europe. Between 2020 and 2024, the value of its turmeric exports to Europe rose from €25 million to €39.9 million (+58.83%). In 2024, India exported more than 18,000 tonnes of turmeric to Europe. Over 60% of these shipments went to Germany, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, with 23% going to Germany alone.

India’s turmeric is prized for its strong yellow colour and high curcumin content – up to 8%. This makes it attractive for food colouring, supplements and functional health products. India also benefits from a vast domestic industry supported by the Spice Board of India. They oversee mandatory testing, promote exports and organise the biennial World Spice Congress. With over 48,000 turmeric shipments annually and more than 3,600 exporters in the supply chain, India is a strong competitor.

One major challenge faced by the Indian turmeric industry is the adulteration of turmeric. This is done by adding lower-cost botanical ingredients, starches, chalk powder, cassava and synthetics. All of these negatively affect the quality.

Peru

Peru is the second-largest turmeric supplier to Europe. It exported 2,739 tonnes of turmeric to the EU in 2024. That represents around 12% of European turmeric imports from developing countries. Although volumes differ, Peru’s export value has increased slightly: from €3.9 million in 2020 to €4.4 million in 2024 (+11.36%). This is partly due to Peru’s emphasis on high-curcumin turmeric and its branding as a superfood.

One of Peru’s key strengths is its institutional support. PromPerú is the national export promotion agency. They have helped position turmeric under the ‘Superfoods from Peru’ banner. It also supports exporters in achieving high-level certifications, including ISO, HACCP, GLOBAL GAP, TESCO and organic standards. PromPerú is active at international trade fairs, too. It operates a trade commission in the UK to connect buyers there with Peruvian suppliers.

However, meeting European regulatory requirements remains challenging for many Peruvian exporters. Apasem Foods, a major Peruvian turmeric and ginger exporter, has increased shipments to the United States. Regulations here are less strict and freight costs are lower. "Many exporters are opting for the US market because it has fewer complications compared to Europe," says company representative Herrera. Despite these challenges, demand for Peruvian organic turmeric powder continues to grow at 10-15% annually, selling for USD 3.7 per kilo.

Madagascar

Experiencing growth in both value and volume, Madagascar exported 315 tonnes of turmeric to Europe in 2024. That was 14.96% more than in 2020. The reported value of those exports was €841,000 (+51.53%). France is the main destination for Malagasy turmeric, receiving over 50% of its exports. This strong preference is most likely linked to historical trade ties and a shared language. France and Germany combined account for 85% of Madagascar’s total export volume.

Madagascar’s turmeric is cultivated in the coastal ‘centre-est’ region, and especially in Beforona. It is valued for its high curcumin content – around 7.5% – and is grown in areas known for rhizome crops like turmeric.

Climate change poses a major threat to turmeric cultivation in Madagascar. Rising temperatures and unpredictable rainfall patterns directly affect crop yields and quality. High poverty levels also drive farmers toward subsistence crops rather than commercial production for export. Other challenges faced by Madagascar include poor infrastructure, which makes it difficult to transport turmeric from farms to ports. In addition, political instability creates uncertainty for investors and exporters. And unsustainable land-management practices such as slash-and-burn agriculture degrade soil quality and reduce long-term productivity.

Indonesia

Indonesia has become one of the fastest-growing exporters of turmeric to Europe. Between 2020 and 2024, those exports increased in value from €130,000 to €456,000 (+250.77%). In volume terms, shipments rose from 60 tonnes to 203 tonnes (+238.33%). Spain and the UK are the main European destinations for Indonesian turmeric, together accounting for more than 75% of exports. Buyers are attracted to Indonesian turmeric for its high curcumin content and consistent quality.

Most of Indonesia’s turmeric exports still go to regional markets such as India, Malaysia and Singapore. Indonesia’s rise shows the value of product quality and targeting high-demand markets. Building relationships with European buyers, especially in Spain and the UK, can unlock opportunities for similarly positioned suppliers.

However, Indonesia faces significant food safety challenges that could affect its reputation as a turmeric exporter. In August 2025, hundreds of people fell ill after consuming contaminated turmeric rice from a government food programme. The authorities are investigating the exact cause, which was most likely either pesticide or heavy metal contamination. This incident shows weaknesses in local food safety systems.

Tips:

- Consider joining the Global Curcumin Association, which offers a range of assistance to exporters of turmeric from developing countries like you.

- Compare your products and company with competitors from other supplying countries. Use the ITC Trade Map to find exporters in each country, then your compare market segments, prices, quality and target countries.

What companies are you competing with?

Your main competitors include established Indian exporters who compete strongly on price, emerging Latin American suppliers who emphasise their sustainability certifications and southeast Asian producers who target both bulk and premium segments.

India

The competitive landscape is strong in India. This puts European importers in a strong position when it comes to negotiating prices. For suppliers, that makes it essential that they stand out through quality, certification and traceability.

MTE Spice focuses on organic turmeric and products with high curcumin content. This firm emphasises the health benefits of turmeric, such as its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. They export both turmeric bulbs and fingers. Diaspora Co. combines storytelling with social responsibility. It promotes traceable, regenerative farming practices and fair partnerships with smallholder farmers. This kind of approach is increasingly appreciated by conscious European buyers.

Other notable exporters include VSR Overseas, Raj Foods and Green Earth Products. All of these serve a range of turmeric markets, including whole, powdered and processed formats.

Peru

Peru’s turmeric exporters are increasingly positioning themselves around sustainability and certification. Supracorp SAC exports turmeric in both bulb and powder form. It highlights its use of polypropylene bags for durability and low cost. La Campiña supplies organic turmeric with multiple certifications, including HACCP, GLOBAL GAP, Demeter, Fairtrade, USDA Organic, EU Organic and Canada Organic. Its marketing includes storytelling and visual branding tailored to international buyers. Algarrobos Organicos del Peru works with eight farming communities in different parts of Peru, supporting more than 500 families in rural areas. Other exporters include Agroexportaciones Llacta.

PromPerú plays a vital role in promoting Peruvian turmeric internationally and in connecting exporters there with buyers in Europe.

Madagascar

Madagascar has a smaller export base, but several of its exporters are known for supplying turmeric to Europe. Phael Flor Export exports fresh, dried and powdered turmeric, along with essential oils. This company emphasises its sustainability and international reach. Jacarandas is a France/Madagascar-based exporter with a strong presence in essential oils and turmeric. It is well-positioned to serve buyers in France and Germany, two of the largest markets for herbal ingredients in Europe.

Indonesia

Indonesia has a growing turmeric export sector, with a focus on both B2B and B2C applications. Subur Anugerah Indonesia exports dried turmeric slices to international buyers. Agrio Spice adds educational content for European consumers by explaining how turmeric can be used in wellness products like lattes and supplements. Other exporters include Spicesnu and Trove Spices, which supplies turmeric in both raw and processed forms.

What products are you competing with?

When exporting turmeric as a food colourant to the EU, you are competing with both natural and synthetic alternative ingredients. Synthetic additives like tartrazine (E102) and quinoline yellow (E104) were once popular. Now they are under increasing regulatory and consumer scrutiny in the European Union.

Synthetic alternatives to turmeric (E100)

Synthetic colourants are strictly regulated in Europe under Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008. Recent updates, such as EFSA’s revised acceptable daily intake for E110, have led to mandatory warning labels for products containing these dyes. Labels now often state: "May have an adverse effect on activity and attention in children". Due to tighter controls and a negative consumer image, these synthetic additives are being phased out of many products in Europe. In particular, these include children’s food, snacks, beverages and health-positioned categories.

Natural alternatives to turmeric (E100)

The main natural alternatives to turmeric include safflower, marigold, orange carrot, palm fruit, fungus (Blakeslea) and annatto. Each has its own colouring compound, seasonal availability and strengths or limitations. The table below shows all the natural alternatives to turmeric, with their strengths, weaknesses and colour range.

Table 6: Natural alternatives to turmeric (E100)

| Source | Main pigment | Colour range | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turmeric | Curcumin | Yellow | Good heat stability, unaffected by pH. | Poor light stability unless encapsulated. Encapsulation can cause cloudiness in beverages and jellies. |

| Safflower | Safflower yellow (carthamin) | Bright yellow | Water-soluble, good for clean-label applications. | Limited colour strength; less versatile across categories. |

| Marigold | Lutein | Neutral yellow | Heat and light stable, pH independent. | Can impart taste in high doses; may require ascorbic acid in high-water-activity foods. |

| Orange carrot | Beta-carotene | Yellow orange | Good heat/light stability, low off flavour, pH independent. | Cloudy in transparent applications; may need ascorbic acid in moist products. |

| Palm fruit | Alpha/beta-carotene | Orange | Stable, pH-resistant, good colouring strength. | Cloudy in some products; sustainability concerns may deter some European buyers. |

| Fungus (Blakeslea) | Natural beta-carotene | Orange | Good heat stability, scalable production, pH independent. | Cloudy in some formulations; requires ascorbic acid in high-water-activity products. |

| Annatto | Bixin (oil-soluble), norbixin (water-soluble) | Yellow orange | Heat stable, pH stable, binds to protein. | Light-sensitive; low pH can cause precipitation unless the formulation is protected. |

Source: ProFound, 2025

Tips:

- Look at how Oterra markets its turmeric compared with other natural yellow colourings. Its turmeric page describes how the crop is grown, the harvest calendar, what curcumin is and its applications in food colouring.

- Emphasise your turmeric’s natural origin and clean-label positioning to European buyers who are looking for alternatives to synthetic dyes with mandatory warning labels.

- Provide technical data on colour performance, heat stability and pH tolerance to demonstrate your turmeric’s advantages in specific food applications.

4. What are the prices of turmeric for food additives in the European market?

Turmeric prices vary a lot, based on curcumin content, processing method, certifications and form (powder or liquid). Prices are negotiated directly with suppliers rather than set by commodity markets. This makes them highly dependent on raw material quality, extraction techniques and market conditions.

Here are some of the main price drivers for turmeric:

- Raw material supply – Weather events like droughts or floods in major producing countries (India, Indonesia, Peru) can directly affect availability and cost;

- Curcumin content – Higher curcumin levels (5-8%) command premium prices due to their stronger colour intensity and reduced dosage requirements;

- Processing method – Solvent-free or steam-extracted oleoresins cost more but meet market demands;

- Certifications – Organic or fair-trade certification typically adds 15-30% to base prices;

- Product quality – Purity, moisture content, particle size and colour consistency determine grade and pricing;

- Logistics – Shipping costs, packaging requirements and currency fluctuations affect final export prices.

Table 7: Turmeric prices in various formats based on online retail data

| Format | Application level | Approx. price per kg (€) |

|---|---|---|

| Lab-grade curcumin powder | Research/pharmaceutical | €1,900+ |

| Liquid curcumin E100 concentrate | Industrial food manufacturing | €82–€100 |

| Powdered curcumin extract | Food manufacturing | €42–€85 |

| Organic turmeric extract | Premium/organic markets | €64+ |

| Standard turmeric powder | General food use | €42–€85 |

Source: ProFound, 2025

Oleoresin formats typically cost more than powdered extracts. They have higher processing requirements and stricter technical standards for both colourant and flavouring applications. European buyers usually want to see updated quotations and a laboratory analysis to go with it before purchase.

Tip:

- Factor certification costs into your long-term pricing strategy. Organic and fair-trade premiums are stable and are increasingly expected by European buyers.

ProFound – Advisers In Development carried out this study on behalf of CBI.

Please review our market information disclaimer.

Search

Enter search terms to find market research