What requirements must herbs and spices meet to be allowed on the European market?

You have to meet a number of requirements to enter the European market. Buyers likely have additional requirements, and they may ask for certificates. Requirements for herbs and spices in Europe are usually about consumer health and safety, but environmental and social sustainability are also becoming more important. If you want to prepare for new legislation and requirements, you need to monitor the market on a regular basis.

Contents of this page

1. What are mandatory requirements for spices and herbs?

Most mandatory requirements for importing herbs and spices (and food in general) are related to food safety. The European Commission Department for Health and Food Safety is responsible for the European Union’s policy and for monitoring the implementation of related laws.

Official food controls

Food imported into the European Union (EU) is subject to official food controls. These controls include regular inspections that can be carried out at import (at the border) or later on, once the food is in the EU, such as at the importer’s premises. The control is meant to check whether the products meet the legal requirements.

An important element of this legislation is that “all food businesses outside Europe, after primary production, must put in place, implement and maintain a procedure based on HACCP principles”. This does not need to be guaranteed with certificates or official controls. However, it shows that an HACCP plan is a key element in the quality management systems of companies aiming to become successful suppliers to the European market.

Non-compliance with European food legislation is reported via the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF). In 2024, 277 issues with spices and herbs were reported in the RASFF. This was slightly higher than the 275 issues reported in 2023. The most common issue was exceeding the Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) for pesticides. The second most common issue was plant toxins, followed by salmonella as the predominant microbiological contamination.

Source: GloballyCool (April 2025)

The main developments visible from Figure 1 can be explained as follows:

- The rise in issues relating to pesticide residue is due mainly to problems with shipments of cumin from India and black pepper from Vietnam. Cumin from India has been subject to stricter conditions since 2023, with an increased testing frequency. This led to a high number of interceptions, which increased the frequency to 30% in January 2025;

- The rise in issues relating to plant toxins is due to issues with oregano from Türkiye and cumin from Türkiye and India. These three product-origins are also subject to increased testing frequencies.

Non-compliance leads to stricter conditions

If imports of a certain product from a specific country repeatedly show non-compliance with European food legislation, the frequency of official controls at the border will increase. These products are listed in Annex 1 of the regulations on the temporary increase of official controls and emergency measures. One example is spice mixes from Pakistan, which are frequently checked due to their increased risk of aflatoxins (aflatoxins come from mould and therefore are part of the mycotoxins group in Figure 1).

Table 1 lists all the herbs and spices that are subject to temporary increases in official controls at entry to the European Union, including the relevant hazards and origins. The last column, ‘notes’ gives more information on specific measures, as they tend to change over time due to changes in risk perceptions. For example, the spice mixes from Pakistan experienced a decrease in the frequency of controls (from 50% to 30%), due to improved test results and an associated reduction in food-safety risks.

Table 1: Herbs and spices subject to temporary increases in official controls in the EU (frequency of identity and physical checks, in %), since 08/01/2025

| Country of origin | China | India | Pakistan | Sri Lanka | Türkiye | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN Code and product name | Hazard | Notes | |||||

| Sweet peppers (Capsicum annuum), ground | Salmonella | 10 | Stable | ||||

| Nutmeg | Aflatoxins | 30 | Stable | ||||

| Capsicum peppers, ground | Aflatoxins | 10 | 50 | For India, since 2023; for Sri Lanka, since January 2025 | |||

| Cumin, all types | Pesticide residues | 30 | Since 2023, but frequency increased to 30% in January 2025 | ||||

| Vanilla | Pesticide residues | 20 | Since July 2024 | ||||

| Cloves | Pesticide residues | 20 | Since July 2024 | ||||

| Spice mixes | Aflatoxins | 30 | Stable, but frequency decreased from 50% to 30% in 2024 | ||||

| Cumin, all types | Pyrrolizidine alkaloids | 0 | Previous frequency of 20%, increased to 30% in 2024, before Turkish cumin became subject to the stricter EU regime in January 2025 (see Table 2). | ||||

| Dried oregano | Pyrrolizidine alkaloids | 30 | Frequency was stable at 20% for a long time, but increased to 30% in January 2025 |

Source: GloballyCool (April 2025), based on EUR-Lex

Another table in EU Regulation 2019/1793 lists products that have special import conditions because of contamination risks. Annex 2 gives special import conditions for food consignments that:

- consist of products that come from multiple origin countries, or;

- contain two or more ingredients from Table 2 (below), and the ingredients make up more than 20% of the total product.

For these consignments, a frequency of identity and physical checks as a percentage is applied to make sure that contamination hazards remain under control. In other words, for the products in Annex 2 (Table 2 below), the import conditions are stricter than for the products of Annex 1.

Table 2: Spices and herbs subject to special conditions for import to the EU (frequency of identity and physical checks, in %)

| Country of origin | Brazil | Ethiopia | Indonesia | India | Sri Lanka | Türkiye | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN Code and product name | Hazard | ||||||

| 0904 - Pepper of the genus Piper, Capsicum or Pimenta | Aflatoxins | 30 | |||||

| Pesticide residues | 20 | ||||||

| 0904 11 00 - Black pepper | Salmonella | 50 | |||||

| 0904 21 10 - Peppers of the genus Capsicum | Aflatoxins | 50 | |||||

| 0904 21 90 – Dried Capsicum or Pimenta, neither crushed nor ground (only a few products) | Aflatoxins | 50 | |||||

| 0904 22 00 - Peppers of the genus Capsicum (only a few products) | Aflatoxins | 50 | |||||

| 0905 - Vanilla | 0 | ||||||

| 0906 - Cinnamon | 20 | ||||||

| 0907 - Cloves | 0 | ||||||

| 0908 - Nutmeg | Aflatoxins | 50 | |||||

| 0908 - Nutmeg, mace, cardamom | Pesticide residues | 30 | |||||

| 0909 - Seeds of anise, badian, fennel, coriander, cumin, caraway, juniper berries | Pesticide residues | 20 | |||||

| 0909 - Cumin | Pyrrolizidine alkaloids | 30 | |||||

| 0910 - Ginger, saffron, turmeric (curcuma), thyme, bay leaves, curry and other spices | Aflatoxins | 30 | |||||

| Pesticide residues | 20 | ||||||

| Curry leaves | Pesticide residues | 50 |

Source: GloballyCool (April 2025), based on EUR-Lex

Recent changes in frequencies include the following:

- The testing frequency for nutmeg from Indonesia was previously 30%, but it increased to 50% in July 2024;

- The testing frequency for pepper (CN 0904) and spices in CN 0910 (ginger, saffron, turmeric) from Ethiopia was previously 50% for testing on Aflatoxins, but it decreased to 30% in July 2024;

- The pesticide-testing frequency for nutmeg, mace and cardamom from India was previously 20%, but it increased to 30% in July 2024;

- Cumin from Turkey was included in this regime from January 2025, with a testing frequency of 30% for Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids.

Tips:

- Stay up to date with updates on official controls on the European Commission website. The list is updated regularly. Even if your country is not on the list, make sure to be aware of the most common contaminations for your products and implement all preventive measures you can;

- Search the RASFF database for examples of withdrawals from the European market;

- Subscribe to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) news (free) to stay updated on European food-safety developments;

- Implement an HACCP system into your daily practice. Even if HACCP is not required in your country, exporting to the EU means you will have to comply with European food safety regulations.

Control of pesticide residues

Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 sets maximum residue levels (MRLs) of pesticides in or on plant-origin food and feed. The MRL is the highest amount of pesticide residue legally permitted in or on food products when pesticides are used. Products exceeding these levels are taken off the European market. In 2024, 47% of all issues reported in the RASFF related to excessive pesticide levels or traces of illegal pesticides.

In 2024, the most frequently reported pesticide issues were:

- Chlorpyrifos 40 issues (30%)

- Pesticide cocktails 35 issues (27%)

- Ethylene oxide (EtO) 16 issues (12%)

- Others 40 issues (30%)

A cocktail is a mix of two or more pesticides, often including Chlorpyrifos and others, such as Anthraquinone, Carbendazim, Chlorfenapyr, Chlorothalonil, Clothianidin, Thiamethoxam, Tolfenpyrad, Triazophos or Cyromazine.

Dehydration factor

When assessing MRLs, the pesticide residues found in dried products must be compared to fresh products. In the case of dried products, Article 20 of Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 allows the concentration caused by the drying process to be considered when determining the MRL. To have a harmonised MRL assessment, the European Spice Association (ESA) has set dehydration factors for dried spices and herbs. This means that the pesticide limit fixed in the Regulation for the fresh product should be multiplied by the dehydration factor. The dehydration factors for the various spices and herbs vary from 3 (for dried garlic) to 13 (for coriander leaves).

The EU regularly updates its list of approved pesticides (Annex 1). In 2022, the European Commission adopted proposals to reduce the use and risk of chemical pesticides by 50% by 2030 (SUR). However, this Sustainable Use of Pesticides Regulation (SUR) plan was withdrawn in February 2024, after being rejected by the European Parliament in November 2023. At the moment of writing (March 2025), the European Commission was still developing a more balanced approach and updated regulation.

Synthetic pesticides not allowed in organic production

The use of synthetic pesticides is not allowed in organic production. Very low residue levels (often 0.01 parts per million) may be tolerated, but only if there is proof that the presence of the pesticide is due to cross-contamination, rather than to illegal pesticide use.

Tips:

- Select your product or the pesticide you use in the EU pesticide database for a list of relevant MRLs;

- Follow the ongoing reviews of MRLs in the EU to prepare for potential changes in MRLs;

- Apply Integrated Pest Management (IPM) to reduce your use of pesticides. This is an agricultural pest control strategy that uses natural control practices in addition to chemical spraying. See the FAO website for more information about IPM;

- Work closely with farmers to manage and reduce the use of pesticides in the cultivation of herbs and spices. Engage plant protection experts who can guide and advise farmers on the sustainable use of pesticides;

- Consider heat treatment instead of EtO fumigation to reduce the risk of insect contamination;

- Become an associate member of the ESA to benefit from its services, networking opportunities and guidance documents.

Control of contaminants

Food contaminants are substances that have not been intentionally added to food. They may be present in herbs and spices as a result of production, packaging, transport, holding or environmental contamination. Contaminants can pose a health risk to consumers. To minimise these risks, the EU has set maximum levels for certain contaminants in food and ingredients.

Bacterial contaminants

The EU regulation on microbiological criteria for foodstuffs lays down the microbiological criteria for certain micro-organisms and the rules that food business operators need to comply with. It does not set specific limits for herbs and spices.

The most common type of bacterial contaminant in spices and herbs is Salmonella. Salmonella must be completely absent in spices and herbs. It is usually transmitted via contaminated irrigation water, manure, hands or animals if products are dried outside. In 2024, almost 10% of all 277 issues reported in the RASFF database related to salmonella.

Black pepper from Brazil is still the largest contributor to the subgroup of salmonella issues, but the number of salmonella issues caused by Brazilian black pepper has decreased drastically – from 45 in 2022 to 18 in 2023, and to only 2 in 2024. This was largely due to a lower export volume to Germany, which has always been the main country reporting these issues in RASFF.

Tips:

- For more information on the EU’s management of food contaminants, take a look at their factsheet on how the EU ensures that our food is safe;

- Comply with the Codex Alimentarius Code of Hygienic Practice for Low Moisture Food (CXC 75-215) and the International Organisation of Spice Trade Association General Guideline for Good Agricultural Practices on Spices & Culinary Herbs to prevent contamination. The latter guideline is available through national or international spice associations. An equivalent guide is available online from the American Spice Trade Association;

- Heat sterilisation is a natural, chemical and radiation-free option that is popular amongst European buyers. Heat sterilisation equipment is quite expensive, so it might be best to use a third party;

- Keep your food safety testing practices up to date, by automating and computerising your processes, for example;

- Follow the latest food safety news from EFSA.

Plant toxins

Since December 2020, following Commission Regulation (EU) 2020/2040, there have been maximum limits put in place for certain foodstuffs containing pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PA). In addition to the limit of 400 μg/kg for cumin seed and most dried herbs, there is a higher limit of 1,000 μg/kg in place for borage, lovage, marjoram, oregano and mixtures of these herbs. The number of reported issues grew from 25 in 2022 to 46 in 2023, and it increased further to 55 in 2024, primarily because of excessive PA levels in oregano and cumin from Türkiye.

Plant toxins can be transmitted to spices and herbs from weeds like:

- ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris);

- Datura stramonium;

- black nightshade (Solanum nigrum) and;

- potato berries.

Mycotoxins

In 2024, approximately 8% of all issues reported in the RASFF database were due to mycotoxins. Mycotoxins are toxic compounds that are naturally produced by fungi, more commonly called moulds. The most common mycotoxins in herbs and spices are aflatoxins and Ochratoxin A. Aflatoxin contamination can take place in several spices including nutmeg, dried chillies, turmeric and ginger. The RASFF database shows that this kind of contamination is frequently found in nutmeg from Indonesia.

To protect consumers, the EU has set aflatoxins and ochratoxin A limits for specific herbs and spices (see Commission Regulation (EC) 1881/2006).

Table 3: Aflatoxin limits for specific spices and herbs in the European Union

| Mycotoxin | Product | Limit (μg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Aflatoxins | Dried chillies and paprika, pepper, nutmeg, ginger, turmeric, mixtures of spices containing one or more of the listed | 5 for B1 10 for sum of B1, B2, G1 and G2 |

| Ochratoxin A | Spices and mixtures of spices (except dried chillies and paprika) | 15 |

| Ochratoxin A | Dried chillies and paprika | 20 |

Source: EUR-Lex (25/05/2023)

Ochratoxin A was the subject of scientific research in the EU between 2018 and 2022. Studies have suggested that ochratoxin A may be genotoxic (causing genetic mutations) and carcinogenic (causing cancer). So far, these studies have not resulted in sharp reductions in the EU’s limits.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH)

Smoke contains polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), most notably benzo(a)pyrene. PAH can increase the risk of cancer. Because of this, the EU has set PAH limits for spices and herbs (except cardamon and smoked Capsicum spp): 10μg/kg for benzo(a)pyrene and 50μg/kg for the sum of all PAHs.

High PAH levels can be the result of high heat, using fossil fuels and/or a long smoking process. Although excessive levels of PAHs in spices and herbs are uncommon, heating and smoking do pose a risk. Crushed spices absorb more smoke than whole spices. The number of issues reported in the RASFF was relatively stable, with 5-6 cases about high PAH levels each year between 2022 and 2024. These cases involved a wide range of spices and herbs, including ginger, paprika, black pepper, turmeric, bay leaves, chillies, garlic and cinnamon.

Metal contaminants

Metals like lead naturally occur in the environment, such as in soil and in water. Pollution from human activity adds to metals being present in the environment too. As a result, metal residues can occur in food. Contamination can happen during food processing and storage.

The EU has had lead residue limits for spices since 2021:

- 0.60 mg/kg for fruit spices;

- 1.5 mg/kg for root and rhizome spices;

- 2.0 mg/kg for bark spices;

- 1.0 mg/kg for bud spices and flower pistil spices;

- 0.9 mg/kg for seed spices.

The number of issues was relatively stable, with 3-5 cases reported each year. Excessive lead was found several times in Vietnamese cinnamon, and lead was also found in batches of turmeric, cinnamon, cardamom, chillies and cloves from Vietnam, Indonesia, Madagascar and Uganda.

Tips:

- Apply integrated pest management practices, such as safe planting distances and early weed removal to prevent plant toxin contamination;

- Minimise the risk of mycotoxin contamination through good agricultural, storage and processing practices. For example, dry your spices and herbs properly – preferably in thin layers – and keep them dry during storage and transport too. Refer to the Codex Alimentarius Code of Practice for the prevention and reduction of mycotoxins in spices. For information on the safe storage and transport of spices and herbs, see the Transport Information Service;

- Check the national legislation in your target countries through the EUAccess2markets ‘My Trade Assistant’ tool. EU legislation only defines maximum levels of aflatoxins for the five spices mentioned above. For other spices, different national legislation on aflatoxins may apply;

- Only use ISO/IEC 17025-accredited laboratories for the control of contaminants in herbs and spices. The presence of aflatoxins must be tested according to the EU regulation on methods of sampling and analysis for the official control of the levels of mycotoxins in foodstuffs;

- Avoid fossil fuels or gas for smoking. Instead, use non-coniferous wood that has not been chemically treated. Refer to the Codex Alimentarius Code of Practice for the reduction of contamination of food with PAH (CXC 68-2009) from smoking and direct drying processes.

Labelling and packaging

The labelling of herbs and spices requires careful attention. The 2024 RASFF overview contains 7 labelling issues (down from 11 in 2023), most of which related to allergens. In a few cases, the allergen declaration was missing, but most concerned an undeclared allergen (celery, mustard, sesame).

Food imported into the EU must meet the legislation on food labelling. Bulk packaging labels must contain:

- Name and variety of product;

- Batch code;

- Net weight in metric system;

- Shelf life of the product or best before date, and recommended storage conditions;

- Lot identification number;

- Country of origin;

- Name and address of the manufacturer, packer, distributor or importer.

The lot identification and the name and address of the manufacturer, packer, distributor or importer may be replaced by an identification mark. Labels can also include details such as brand, drying method and harvest date. These batch details can also be included in the Product Data Sheet.

If the imported product is going directly to retail, the product labelling must meet EU regulations regarding the provision of food information to consumers. These regulations include clear requirements for nutrition values, origin, allergen labelling and the minimum font size for mandatory information. For herbs and spices, the label must declare allergens, such as celery and mustard. Spice mixes might also contain allergens, including gluten, wheat and nuts. Additionally, sulphur dioxide – sometimes used as a preservative – must be declared as an allergen.

Tips:

- Read how to label your product on Food and Drink Industry Ireland’s practical guide to food labelling;

- Get an idea of what a Product Data Sheet can look like by taking a look at this example for organic nutmeg powder;

- Take all possible forms of allergen contamination into account for the allergen declaration on the label;

- Ask your buyer to approve your concept before you print your labels;

- See CBIs product studies for product-specific packaging requirements;

- Contact Open Trade Gate Sweden if you have specific questions regarding rules and requirements in Sweden and the EU.

Control of unauthorised agents

The EU has strict regulations on what substances are allowed in foods. This is to ensure safe food for consumers. Regulation 1333/2008 establishes the overall framework for the use of food additives in the EU. This regulation contains a list of approved food additives and their permitted uses, as well as labelling rules. Regulation 231/2012 provides additional, detailed purity criteria for food additives. It lists the specific chemical composition, purity standards and production methods that approved additives must meet.

For spices and spice mixes, the restrictions for colouring agents are especially relevant. Of the 277 issues reported in the RASFF for 2024, 7 concerned the unauthorised use of colouring agents. This was about the same as in 2023, but it was significantly less than the total of 16 in 2022. Examples of colouring agents found in spice mixes include Sudan I, II and IV, as well as Rhodamine B.

Fighting adulteration

Another issue is the adulteration of herbs and spices. The more valuable the product, the more likely adulteration is. Examples are vanilla extract made from tonka beans, oregano mixed with strawberry leaves and saffron mixed with cheap components.

Several organisations and projects have launched initiatives to fight food fraud. The ESA has published an Adulteration Awareness Document (available to ESA members), and the UK Spice and Seasoning Association offers guidance on the authenticity of herbs and spices.

Tips:

- Read more about additives for spices and herbs in section 12 of the Food Additives Regulation 1333/2008;

- Use Annex II of the EU Food Additives Regulation to check which food additives are allowed in Europe;

- Follow the re-evaluation of food additives to prepare for potential changes in food additive limits;

- Watch the CBI masterclass on food fraud and the CBI webinar on avoiding border rejections.

Phytosanitary inspection

The EU inspects food products to protect citizens, animals and plants from diseases and pests. Common tools are food inspections and phytosanitary certificates. Special phytosanitary certificates are issued for plants or plant products that can be reproduced within Europe after import, such as for food containing seeds. Traders of herbs and spices require phytosanitary certificates only for seeds used for sowing and for fresh herbs and spices, such as fresh garlic, ginger and herbs. For more details on exporting fresh herbs to Europe, read the CBI’s study about exporting fresh herbs to Europe.

2. What additional requirements and certifications do buyers ask for in spices and herbs?

European buyers often have additional requirements, beyond legal obligations. Many of these requirements concern the European Spice Association (ESA) quality minima for specific products. Others relate to food safety, and sustainable and ethical business practices.

Product quality requirements

Product quality is a key issue for European buyers. Several factors determine the quality of spices and herbs, including subjective aspects, like flavour and colour. Buyers often ask suppliers to comply with the ESA quality minima (available to ESA members only).

While the applied quality criteria vary by product, several are used for all herbs and spices:

Cleanliness or purity

Herbs and spices must be free from diseases, foreign matter, foreign odours and other issues. The ESA sets the maximum presence of external matter at 10 g/kg, and foreign objects should be smaller than 2mm in diameter. Some buyers use more specific indicators from the American Spice Trade Association (ASTA) Cleanliness Specifications. These can include the maximum presence of dead insects, excreta, moulds and other foreign matter. Other indicators in this category include ash level and acidity.

Moisture content

The ESA also sets the minimum moisture content for different spices and herbs. Some buyers may ask for a different moisture content.

Mesh or particle size of ground spices

To measure particle size, spices and herbs are ground to pass through a sieve of a specific diameter, expressed in microns. 95–99.5% of the powder should pass through the specified sieve size.

Odour and flavour

Herbs and spices must have a characteristic odour and flavour. This mainly depends on the chemical components of the essential oil. The variety and cultivar also have an effect, as do the geographic, climatic and growth conditions.

Essential oil

The quality of spices and herbs is typically better when the ash percentage is low and the essential oil content is high. ESA sets a minimum essential oil content for most spices and herbs.

For several spices and herbs, internationally recognised standards set specific criteria for quality and specification:

- Codex Alimentarius runs a committee on spices and culinary herbs (CCSCH) with standards developed for 14 different types of spices and herbs. Most of these standards were published in 2022, and a few were added in 2024: for small cardamom, for allspice, juniper berry and star anise, and for curcuma;

- The International Standards Organisation (ISO) has product specifications for various spices, culinary herbs and condiments. The most recent specifications developed were for fennel (2023) and for sumac (2022).

Tips:

- Ask your buyer for a Product Data Sheet so you can learn about the product requirements;

- Take preventative measures, such as heat treatment or fumigation against contamination with insects. Do not use banned fumigants such as ethylene oxide;

- Apply careful physical sorting and eye-hand control practices to check for foreign bodies in your products;

- Use optical, metal and similar detectors as extra security to protect against contamination by foreign bodies.

Irradiation

Irradiation is not often used for spices and herbs. Although the EU allows sterilisation by irradiation under the condition of labelling, European consumers do not appreciate irradiated food. Because of this, European buyers often require radioactivity contamination tests for imported spices and herbs.

Third-party laboratory tests

The microbiological, chemical and physical conditions of the product are so important to buyers, that they increasingly ask for laboratory test reports. Buyers from Northwest Europe may request testing for more than 500 different pesticide residues. Deliveries are commonly accompanied by documentation from accredited laboratories. These documents should not be older than six months.

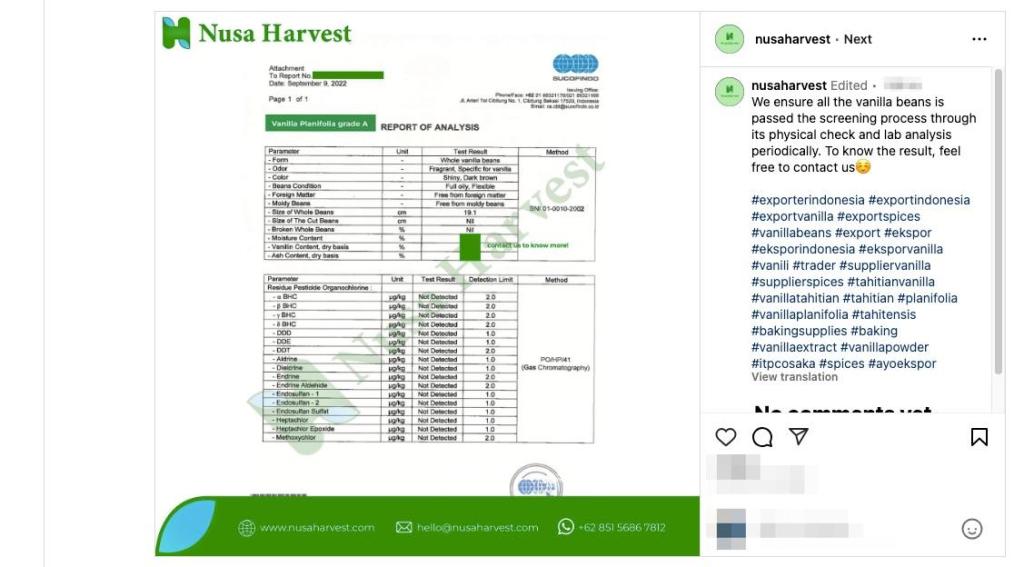

The laboratories must be accredited, which can be an issue for suppliers in some developing counties. In some countries, laboratories can only perform a limited number of tests, so they need to send samples to other countries for analysis. The Indonesian company Nusa Harvest found the local laboratory SUCOFINDO to do the analysis of a batch of vanilla beans and posted the first page of the analysis report on Instagram.

Figure 2: Instagram post from Nusa Harvest showing lab-analysis results

Source: Nusa @ Instagram

Tips:

- Agree on the laboratory with your buyer and the analytical test methods used;

- Follow ASTA’s Good Manufacturing Practice Guide for Spices;

- Get food safety certification. Check which food safety certification company to consult with your buyers. Examples include SGS and Eurofins;

- Sample according to the European sampling regulations.

Food safety certification

Food safety is crucial for the European market. Although legislation addresses many potential risks, it is not enough on its own. The 277 issues reported in the RASFF database in 2024 show that problems can still occur. As a result, importers prefer to work with producers and exporters who have food-safety systems with certificates recognised by the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI).

For processors and traders of spices and herbs operating internationally, the most widely accepted certification programme is the Food Safety System Certification (FSSC 22000). This is a third-party certification programme based on the ISO methodology.

Sooner or later, exporters to Europe are likely to come across buyers who require certification from the International Featured Standards (IFS) or British Retail Consortium Global Standards (BRCGS). These certification programmes are particularly relevant if you target certain European food-retail markets.

Having programmes with third-party certification is an asset to your company, and it helps attract new buyers. However, serious buyers may also want to visit and audit the production facilities of potential suppliers.

Sustainability compliance

Although less important than product and food safety requirements, social and environmental compliance is increasingly demanded by European buyers. This often means that suppliers have to undersign the buyer’s code of conduct. Buyers may also ask for certification from a third-party scheme like Rainforest Alliance.

Codes of conduct

Codes of conduct (CoC) vary from company to company, but they are often similar in structure and the issues they cover. In 2022, the ESA published guidelines for their members. Since a lot of European herb and spice companies are members of the ESA, you will likely come across these guidelines sooner or later. Under this sustainability code of conduct, ESA members monitor their own operations and those of their suppliers on a range of social and environmental criteria.

Third-party certification: Rainforest Alliance and B Corp

Several third-party certification schemes set criteria for both social and environmental issues. The most important ones are Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade and B Corp. For companies with FSSC22000 certification, it might also be worthwhile to consider the social-sustainability certification FSSC24000.

The Rainforest Alliance is quite a common certification scheme applied in mainstream agricultural value chains. Since 2022, the Rainforest Alliance and the Union for Ethical BioTrade (UEBT) have had a joint Herbs & Spices Programme in place. There are two types of certifications in this programme:

- Farm certification, with the UEBT/Rainforest Alliance requirements compiled in a Field Checklist and two system checklists: one for organisations in sourcing areas and another for organisations elsewhere;

- Supply chain certification, in which companies that buy from certified farms have to meet the Rainforest Alliance 2020 Sustainable Agriculture Standard’s Supply Chain Requirements.

Probably the fastest growing sustainability certification scheme is B Corp. Fairtrade certification – which we discussed in the chapter on requirements for niche markets – ensures that individual products meet high social and environmental standards. In contrast, B Corp certifies entire companies in a comprehensive and demanding way. B Corp certification requires companies meet high standards of performance, accountability and transparency on a wide range of factors.

These factors include:

- employee benefits;

- charitable giving;

- supply chain practices, and;

- input materials.

Companies can acquire the B Corp certificate by:

- Demonstrating they have high social and environmental performance. The company must achieve what is known as a ‘B Impact Assessment score’ of 80 or above and pass a risk review;

- Making a legal commitment by changing the corporate governance structure to be accountable to all stakeholders and not just shareholders;

- Being transparent by allowing information about the company’s performance on the standards to be publicly available on their B Corp profile on B Lab’s website.

Transparency initiatives

The Supplier Ethical Data Exchange (Sedex) is a well-known global initiative that aims to make global supply chains more transparent. Sedex is a global, collaborative forum for buyers, suppliers and auditors to store and share information. Sedex offers participating companies tools (like the SMETA audit template) for managing sustainability performance. Unlike certification programmes that specify third-party audits and certification by definition, the Sedex tools can manage sustainability performance through first-party or second-party audits.

The aim of sharing all this information is to manage performance on sustainability. This covers labour rights, health and safety, the environment and business ethics. As such, Sedex is not a certifiable scheme nor a standard-setting body. By participating in this platform, companies show their willingness to share data and use information to manage and improve ethical standards in the supply chain.

The Sedex organisation has also developed social auditing standards: the ‘SMETA’ (Sedex Members Ethical Trade Audit). This auditing template helps companies to assess suppliers’ working conditions in the social, ethical, and environmental domains.

SSI aims to transform the global spice industry

Since 2012, the most important sustainable industry initiative in Europe has been the Sustainable Spice Initiative (SSI). This initiative aims to transform the conventional and mainstream global spice industry. It unites companies involved in the herbs and spices sector along with non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Member companies commit to sourcing their products sustainably and making a positive difference throughout their supply chains.

Rather than developing its own standard, SSI operates with a ‘basket of standards’ from which members can choose in order to meet their sustainability commitments. To be included in this ‘basket’, a standard must undergo the SSI benchmarking process and meet specific requirements for strictness and readiness. For this purpose, SSI uses the SAI FSA 3.0 benchmark to compare and assess sustainability certifications. From 2026 onwards, only certifications with FSA 3.0 benchmark silver-level will be recognised. Until then, bronze-level certifications will remain in the basket of standards.

In addition to large spice companies in Europe and America, SSI members include spice exporters from developing countries.

Overview of certifications and CoC

Table 3 provides the most important certifications and codes of conduct for the herbs and spices sector, along with information about the costs and the process. Note that some important costs components of certification are ‘hidden.’ This means that these are hard to quantify, but you will likely find them in the offer of potential service providers. The most important hidden costs are:

- Travel costs for the auditors – time and expenses;

- Accommodation costs for the auditors;

- Non-Conformity/Corrective Action Review.

In addition, it should be clear that any preparation for certification may require you to invest in your facilities or quality assurance and control system.

Last but not least, if a company is applying for certification against different schemes with the same certification body, the certification body will likely be able to offer a discount on the total certification costs.

Table 4: Most important certifications and CoC requested by buyers in the herbs and spices sector

| Name | Type | Cost of companies | Most used in European end-market (s) | Further information on getting certification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sedex Members Ethical Trade Audit (SMETA) | Social audit focused on working conditions | Membership fee: £195/site. Audits typically cost €800–€1,200 for SMEs, but the price is highly dependent on person-day rates and travel costs. | Europe | More information about the process: SMETA guidance document. |

| Rainforest Alliance | Sustainability, including working conditions and environmental criteria | No fixed fee. Costs set by certifier + volume-based royalty. Certified farmers may have reduced premiums. | Northwest Europe | Find a certification body. |

| Food Safety System Certification (FSSC 22000) | Food safety | No fixed fee and highly dependent on person-day rates and travel costs. Costs vary from €1,500 to €3,500 for companies with <20 employees, excluding surveillance audits. Certificates are valid for 3 years. | Northwest Europe | Service providers: conformity assessment bodies. |

| British Retail Consortium Global Standards (BRCGS) | Food safety for suppliers to some UK food retailers | No fixed fee and highly dependent on person-day rates and travel costs. Annual BRCGS service fee: £725. | Northwest Europe | Find consultants.

|

| International Featured Standards (IFS) | Food safety for suppliers to food retail | No fixed fee and highly dependent on person-day rates and travel costs. Yearly recertification. | Northwest Europe | More information about the process: IFS portal. |

| Fairtrade | Sustainability, including working conditions, environment, and ethical trade criteria. | No fixed fee. About €3,000/year for SMEs (20 employees, 2 products), however it is highly dependent on person-day rates and travel costs. Certification may yield premium prices. | Northwest Europe | First assessment of potential certification costs: FLOCERT Cost Calculator. |

| B Corp | Social and environmental criteria: employee benefits, charitable giving, supply chain practices, input materials. | $600 annual fee for African SMEs (<$150k USD turnover). $100 assessment fee, deductible from annual fee. | Globally | Get more familiar with B Corp certification via their YouTube videos, such as this introduction to B Corp. Read the B Corp small enterprise guide to get an idea of how to become ready for B Corp certification. Check the B Global Network to find the B Corp contact point in your region or country. |

| EU Organic | Environmental criteria | Average €1,000/year for SMEs. Relatively lower costs for smallholder farmer groups with an internal control system (ICS) up to 2000 farmers. Renewed yearly. | Northwest Europe | Find authorised control bodies by country. |

Source: GloballyCool (March 2025)

Tips:

- Read CBI’s Tips on how to become more socially responsible in the spices and herbs sector to get an update on trends and developments in social compliance;

- Consider implementing a management system focussing on or incorporating sustainable or ethically responsible production;

- Ask your farmers to fill out the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative’s Farmer Self-Assessment Questionnaire to check how sustainable their production is.

3. What are the requirements and certifications for spices and herbs niche markets?

Most additional buyer requirements apply to mainstream herb and spice markets. However, some niche markets have their own, specific requirements. While Fairtrade lays down requirements for sustainability in the social, environmental and ethical domains, product certification for the organic market mainly focuses on environmental requirements.

Sustainability certification

Although it is less important than product and food safety requirements, European buyers are increasingly demanding sustainability. The most obvious market in Europe for sustainably sourced products is the fairtrade market.

Fairtrade

The fairtrade market is built on fairtrade certification. Every player in the supply chain needs to be certified to participate in this market. The fairtrade market is privately regulated.

In the global fairtrade market, there are several fairtrade certification organisations. Fairtrade International is the largest one. It gives you access to the European market and most other international markets, except the United States of America. An example of a smaller, more regional certification organisation is Fairtrade Original from the Netherlands.

Fairtrade International has specific standards for herbs, herbal teas and spices from small-scale producer organisations. This defines minimum prices and price premiums for conventional and organic products from several countries and regions. For herbs and spices without a fixed Fairtrade Minimum Price or fixed Fairtrade Premium, the Fairtrade Premium is set at 15% of the commercial price.

Tips:

- Watch Fairtrade International’s videos to learn more about the Fairtrade system;

- Check Fairtrade International’s standard for herbs, herbal teas and spices, as well as other Fair Trade Standards relevant to your production, processing and trade.

Organic certification

If you want to sell your herbs and spices as organic in Europe, they must be grown using organic production methods that comply with EU organic legislation (Regulation (EU) 2021/2306 supplementing Regulation (EU) 2018/848). Growing and processing facilities must be audited by an accredited certifier. Regulation (EU) 1235/2008 lists requirements for organic products to be imported to the EU from third countries.

The certification procedure roughly follows these five steps:

- Develop an organic farm management plan and implement organic production practices step-by-step. Familiarise yourself with the requirements for organic production and if possible, use local consultancy services;

- Apply for certification when you meet the requirements. Select and negotiate a certification fee with an EU-recognised control body listed in Annex III of Regulation (EU) 1235/2008;

- Arrange for inspection. An inspector verifies whether your organic farm management plan is true to reality. If they find critical non-conformities, you must correct these;

- Become certified. If you have completed Step 3 successfully, a certificate will be issued, valid for one year. You can then put the EU organic logo on your products. You have to print the certifier code number together with the logo;

- Manage batch documentation. Each batch of organic products imported into the EU must be accompanied by an electronic certificate of inspection (e‑COI), as defined in Annex V of Regulation (EC) No 1235/2008. This electronic certificate of inspection has to be generated via the Trade Control and Expert System (TRACES).

Dual certification

Dual certification is a clear asset in both the European fairtrade and organic markets. Consumers in these markets are typically more conscious than mainstream consumers. Because of that, they are more likely to appreciate and buy products that have both a fairtrade and an organic certification logo.

Examples of spices and herbs producers that have obtained both organic and fairtrade certification are:

- Ceylbee International from Sri Lanka. Their spice products include pepper and cinnamon. In addition to the Fairtrade certificate, the company has organic certification for the EU, USA, Japan and Malaysia;

- Shochoch Trading from Ethiopia produces and exports coffee, honey and spices. Their range of spices consists of turmeric and ginger (both fresh and dry), bird’s eye chilli, black cardamom, black pepper, and long pepper and herbs. Their ginger and turmeric bear the fairtrade logo;

- Pure Life from Egypt is a producer and exporter that holds a fairtrade certificate for a wide range of dried herbs of Egyptian origin. They trade both organic-certified herbs (but not for the European market) and non-organic herbs.

Figure 3: Promotional video of the Indonesian dual-certified spice producer Mega Inovasi Organik

Source: Mega Inovasi Organik @ YouTube

Tips:

- Consider investing in organic production. Make a cost-benefit analysis to determine if it is worthwhile for you. Investigate the market potential and potential customers. Even if demand is growing, you need to know what the price premium will be and if it compensates for production costs, which are likely to be higher;

- Find a potential customer who is interested in your organically certified herbs and spices (either actual or hypothetical). Engage them in the process and ask for support where relevant, such as for the batch documentation procedure;

- Try to combine organic certification with other sustainable initiatives (dual certification) to increase your competitiveness.

- Check the guidelines for the imports of organic products into the EU to familiarise yourself with the requirements for European traders;

- Consult ITC Standards Map for a full overview of relevant certification schemes and their requirements.

Globally Cool carried out this study on behalf of CBI.

Please review our market information disclaimer.

Search

Enter search terms to find market research